‘Obviously’, ‘of course’ and ‘it’s quite simple really’. Or how to help children understand what you are saying, with help from Bob Dylan, Billy Bragg, and a host of trainspotters, birdwatchers and naturists!

Date posted: Friday 11th April 2014

I want to make it absolutely crystal clear that I have no objection to folk singers, birdwatchers or naturists. Although they all feature in this post, my aim is to explore how we can help people understand what we mean, without purposely or inadvertently confusing them or putting them down. So here goes…

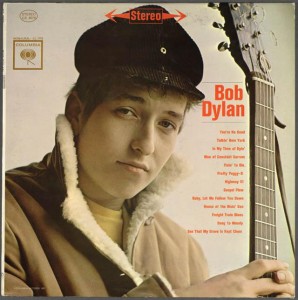

One of the key moments in popular music history took place when Bob Dylan went electric at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival. As with anything connected with Dylan, this event has become legendary and mired in controversy. The bare bones of the story are that since 1963 Bob Dylan had been the darling of the US folk music establishment. He had been hugely influenced by left-wing singer/songwriter Woody Guthrie and was an international success with hits like songs like Blowin’ in the Wind and The Times They are a Changin’. Dylan had been adopted as the unofficial spokesperson for many Americans who were opposed to the United States’ aggressive foreign policy and who were also supportive of the Civil Rights movement. The problem was that many of these millions were dyed-in-the-wool folk music enthusiasts, who were obsessed with exploring the roots of US folk songs and maintaining what they saw as traditional music’s purity. As well as being dyed-in-the-wool, the male folkies (and the movement was dominated by men) wore sensible woollen sweaters, sported goatee beards, smoked pipes and, above all, only garnered respect if they wore a cap that made them look like the skipper of a small lobster fishing boat.

Dylan 1963: When the boat comes in? The world is his lobster? |

Dylan 1965: Folk off? |

By 1965 Dylan had surrounded himself by top-flight musicians who were experimenting with electric blues and what was to become known as ‘rock’. Dylan had appeared at the festival before, wowing the folk fans with his acoustic set, terrible haircut and tatty checked shirt. (Not only had he sung about poor downtrodden agricultural workers, he even looked like one. He basically looked and sounded like a clone of his hero and musical influence, Woody Guthrie.)

By 1965 Dylan had changed. What strikes me was that Dylan not only sounded different, but he looked amazing. He’d stopped pretending to be Woody Guthrie and become a rocker with cool shades, long hair, black leather jacket, a Fender Stratocaster and a cracking backing band. He was still interested in singing about ‘issues’ but had expanded his repertoire to include stream of consciousness songs that only made any sense to himself, but left the fans with endless opportunities for discussing his work. Maggie’s Farm, which he sang as an opener to his 15-minute set at Newport, was thought to be about his rejection of the folk music establishment and the straightjacket they were putting on him and popular music in general. (Equally it could be about a terrible B&B he stayed in, but that’s Dylan for you. After all, there was no TripAdvisor in those days.) Unfortunately he also stopped writing romantically about being nice to girls, and introduced us to a long line of misogynistic songs about how awful his latest girlfriend was and why he was going to dump her. He must have infuriated anyone in the audience wearing a checked shirt, skipper’s cap and a sensible sweater and who was in the process of filling his pipe with shag.

History tells us that Dylan and his electric band played loud rock and were booed off stage after 15 minutes. Eventually he was persuaded to come back on to sing some acoustic numbers, but the damage was done. For some of the audience, and folk aficionados the world over, he might as well have sprayed them with bullets. But even the people who were there are divided about what actually happened. Was there any booing? Why did people boo? There’s even a suggestion that people were yelling for ‘more’, but that because the vowels in ‘more’ and ‘boo’ sound the same, Dylan must have gotten the wrong message.

Dylan at Newport: Boo? More? Or even ‘moo’? Sooner or later one of us must know.

Throughout the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, you could always spot a Sixth Form folk music buff from 100 metres. While everyone else had long hair, wore flared denim jeans and every colour under the sun, the Folkies were determinedly wearing brown cords, trying to grow goatee beards, smoking pipes and sporting horn-rimmed spectacles. And of course they all wore the dreaded lobster skippers’ cap.They had a haughty smugness about them. But what really set them apart from the other boys was how they talked. If they heard the merest hint of Simon and Garfunkel blowing in the wind they would launch into a sarcastic tirade against the duo. A typical slagging off would go something like this. ‘Of course it’s patently obvious to anyone with even the minutest knowledge of popular music that those two are just aping the English Folk idiom. Of course you realise that The Boxer was derived from a sixteenth century Cumbrian Drovers’ paean to his dying heifer.’ Or at the drop of a lobster skipper’s hat they would lecture you on why The Lincolnshire Poacher is so brilliant: but obviously, if you think about it, and it’s quite simple really that anyone with even a smattering of knowledge about true folk music will tell you that it’s actually, as a matter of fact, quite plainly and obviously a derivative of the old Welsh shepherds’ ballad Get Off My Land You Buggers.

Actually, I quite liked folk music, but what I really objected to, and still rankle against, is people who use words and phrases like obviously/of course/if you think about it/ you do realise that. You could argue that it’s harmless, and is much the same as people habitually using phrases like you know/ like/ I mean/sort of as fillers when they are thinking of what to say next or are feeling a bit self-conscious when they are talking. But I think there is a big difference. If someone in authority- or especially if they are setting themselves up as an authority- starts to use obviously and of course and it goes without saying all the time, it means that they are trying to put the listener down. The speaker will know that you don’t know what they are talking about, and by saying that it’s obvious, they are making you out to be a bit of a thicko, in the hope that you will feel insecure and admire them all the more for their vast knowledge.

You might think I’m being a bit sensitive. I don’t think so. Next time you are in a secondary school lesson or in a university lecture, or at a conference, or listening to some academic being interviewed by Melvyn Bragg on In Our Time, or taking part in The Moral Maze, you listen out for the number of times obviously and of course are used. The answer will be a lot. In my time I have met train spotters, birdwatchers, naturists and other members of what on the surface seem to be slightly daft or obsessive groups. When you get talking to them, you will often hear them- and it is usually only men who do it- saying things like: ‘It’s quite simple really. If you think about it, there is only one main distinguishing feature between a cormorant and a shag.’ Or ‘Of course the booby is impressive but everyone knows that the hoopoe has the finest flight pattern.’ They do it in an attempt to assert their superiority over you. To them, it’s a sign that they have the knowledge that allows them to be part of their exclusive club. However I suspect it’s actually a sign of their underlying insecurity.

Ironically, some of the worst offenders for using these types of put downs are Bob Dylan fans themselves. I had the unfortunate experience once of being invited to a meeting of some obscure Dylan fan club. There was massive excitement that they had been able to get a speaker for their annual conference, who was bringing along a rare copy of Dylan’s terrible (to my eyes and ears) feature film Renaldo and Clara… in Swedish! The guys I spoke to (there were no women present) were utterly focused on scoring points off each other by talking about the minutiae of Dylan’s life and the possible meaning of virtually every line of his most obscure tracks. The phrases obviously and of course and the dreaded if you think about it were very much in evidence. It was just horrific.

Billy Bragg: The one-man Clash

Which is why I was a tad anxious about going to a Billy Bragg gig at Cecil Sharp House in Camden Town. As I’m sure everyone knows, Cecil Sharp House is the heart of the UK’s Folk Music scene, and the bastion of all obsessive folk song cataloguers. There you can find the true provenance of The Lincolnshire Poacher, and probably The Lincolnshire Sausage and Poached Egg if you have time. Would Billy drone on incessantly about the roots of each of his songs? Would he stick his finger in his ear? Or would he wear a fisherman’s hat? Not at all. He took us through two and a half hours of his versions of Woody Guthrie songs that Woody never got round to adding music to. Billy did talk about the roots of popular music, but summed it up in one sentence: “Basically, (not a good start, I must admit) the great thing about traditional music is that musicians can use these tunes, ideas and words without having to worry about accidentally on purpose ripping someone else off.” Now that’s what I call socialism.

Billy Bragg: a traditional Drovers’ lament about droving from London to Southend?

So after all this it will probably come as no surprise to you to understand why, when I was performing my Dylan impersonation at an open mike night at a naturist folk club for birdwatchers and steam train enthusiasts, I was not best pleased when the MC approached me and said, “Of course you do realise that sunglasses are regarded as clothes here. But obviously, like me, we do allow folk singers to wear a skipper’s hat.” I sang Maggie’s Farm and left the stage to a chorus of boos.

The main reason why I mention this in such detail is that we do need to be very aware when we are talking with young children, and older children and teenagers with additional learning needs, that we make sure that what we say is what we mean, and to cut out all the useless flannel in our speech, if you know what I mean. Obviously, I’m going to explore this in more detail in the next post.

Take care out there!

Michael

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j4xoxFrRA2Q

Sign up for Michael's weekly blog post by clicking here!

Another great post!

Hi Karen!

Thank you.

Are you in the US now?

Love from Michael (obviously!)